The march in commemoration and protest of the disappearances of the 43 students from the Raul Isidro Burgos Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa brought thousands of protestors to the streets of downtown Mexico City this past Saturday, Sept. 25, 2015. The march was alive with music, performances, banners and chants in an act of memory and resistance in movement.

The collective demand: Justice. After a year of seeking their children, the parents expect results in the investigations and Mexican society has once again affirmed that it’s forbidden to forget the 43.

Thousands of young people marched, mostly university students but also from high school and junior high and even children. Mexican youth has born the brunt of state violence and over the past three years hundreds have been arbitrarily arrested, assassinated and, like in the case of the students from Ayotzinapa, disappeared.

Youth Under Siege

Under Felipe Calderon, the militarization of Mexican cities and countryside with the deployment of thousands of armed forces led to a rapid deterioration in public safety. The country saw a rise in arrests and violence against youth. Many of them were criminalized and wrongly identified as members of organized crime, a tactic to legitimize use of unwarranted public force against them.

Only three months before the attacks in Iguala, Guerrero last year, 22 young people were shot and killed in Tlatlaya in the State of Mexico by an Army unit. They were attacked under the allegations that they belonged to a gang that crossed over the border from Guerrero. According to reports, weapons appear to have been placed on the corpses in positions to simulate a battle. Then-Attorney General Murillo Karam, now infamous throughout the world for his mishandling of the Ayotzinapa case, reported that rogue soldiers killed 8 of the youth and all the others died in a shootout. Witnesses dispute this version and the case is still under investigation.

The Tlatlaya executions are just one example of how the legacy of violence of the Calderon term continues under the Peña Nieto administration. These cases of disappearances and assassinations are extreme expressions of a general assault on youth seen in recent years.

The criminalization of social protest has greatly affected the wellbeing of youth and has had a negative impact on democratic freedoms in Mexico. According to the Front for Freedom of Expression and Social Protest’s report on Control of Public Space, violence against youth has increased under Peña Nieto since December 2012. This includes the criminalization of protest, arbitrary detention and attacks on journalists and human rights defenders.

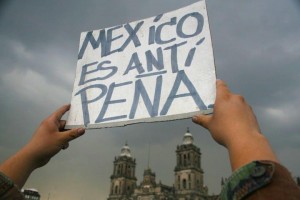

#YoSoy132 and Enrique Peña Nieto Presidency

Enrique Peña Nieto’s political track record of repression of grassroots movements as governor of the State of Mexico was warning of the negative implications that an electoral win would have on human rights and democracy. The student movement #YoSoy132 was formed in 2012 to protest his taking the highest office in the nation.

Enrique Peña Nieto’s political track record of repression of grassroots movements as governor of the State of Mexico was warning of the negative implications that an electoral win would have on human rights and democracy. The student movement #YoSoy132 was formed in 2012 to protest his taking the highest office in the nation.

Within a time span of about seven months, from May to December of that year, the movement mobilized thousands of Mexicans and people globally to reject Peña’s candidacy, call for clean elections, democratization of the Mexican media and a slew of demands based on anti-neoliberalism, democracy, and justice.

The movement was sparked by a spontaneous but well organized student protest in the Iberoamerican University in Mexico City during a campaign talk organized for Peña Nieto on campus. Students of the university disrupted the talk with chants denouncing his responsibility for the repression in Atenco in the State of Mexico in 2006, where an attack by state and federal police resulted in two dead, beatings, house raids and a number of women sexually abused and raped in custody.

During the event in the Iberoamerican University, students shouted at Peña Nieto, asking about the Atenco repression and questioned his responsibility as then-governor of the State of Mexico. Peña Nieto responded by saying that he had used legitimate force to restore peace and order and took full responsibility for the violent confrontation. The students booed the presidential candidate off the stage and the auditorium erupted with the chant “Out with Peña!” while they waved posters that read “Murderer!” and “We will not forget Atenco!”

The university students began a global movement with their spontaneous protest against the repression. The video went viral and when the PRI party tried to assign responsibility to paid political agitators, 131 students from Iberoamerican University created a YouTube video that inspired youth all over the country to organize under the #YoSoy132 hashtag, beginning the movement that bore that name.

Interviewed in 2012, Alinna Rosa Duarte, International Relations student at UNAM explained why hundreds of thousands of students throughout the country opposed Peña Nieto’s candidacy. “We are anti-Peña Nieto because Peña Nieto is anti-youth. Peña Nieto’s party has always been anti-youth. We are a generation that seen crisis after crisis. We are a generation nurtured in neoliberalism, survivors of the Miguel de la Madrid, Carlos Salinas and Ernesto Zedillo presidencies. We are witnesses to repression in Acteal and Atenco. But we are also a generation that is now mobilizing memory against Enrique Peña Nieto, the PRI, and a neoliberal system that has wrought violence and injustice in our country.”

At the core of the movement was a call to Mexican society to mobilize based on the historical memory of the corruption and violence of Peña Nieto’s party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and to act to prevent future violence and a retrocession of an already weak democracy. In the end, Enrique Peña Nieto relied on his well-groomed appearance (including a recent marriage to a soap opera actress) and the implementation of vote buying-exemplified by the distribution of Soriana grocery cards-to win the elections.

At the core of the movement was a call to Mexican society to mobilize based on the historical memory of the corruption and violence of Peña Nieto’s party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), and to act to prevent future violence and a retrocession of an already weak democracy. In the end, Enrique Peña Nieto relied on his well-groomed appearance (including a recent marriage to a soap opera actress) and the implementation of vote buying-exemplified by the distribution of Soriana grocery cards-to win the elections.

On Dec. 1, 2012, the day of his inauguration, thousands of participants of #YoSoy132 and members of the general population took to the streets globally to protest what they considered a political and electoral imposition.

In Mexico City, what started as a peaceful protest from multiple points in the city turned into a violent attack on protestors by police.

Lines of riot police closed down streets around the Bellas Artes Palace, preventing a segment of the march from reaching the Zocalo Square. Ninety-six otherwise peaceful protestors and civilians were arrested on charges of disturbing the peace. The next day all but 14 detainees were released. The rest, identified as political prisoners by human rights organizations, were released twenty-seven days later.

Remembered as #1DMX, the confrontations and violence against protestors and bystanders who were also arbitrarily detained shocked many people used to a general respect for protests in the capital city. It marked the new administration of Miguel Angel Mancera and served as a sign of times to come.

Criminalization of Social Protest Since 2012

#1DMX marked a shift toward an increase in the criminalization of social protest in the capital, a trend that has affected youth activists in the last three years. According to Services and Consultancy for Peace (SERAPAZ) and the Front for Freedom of Expression and Social Protest, since 2012 Mexico has witnessed a return to authoritarian practices while increased violence has affected the exercise of democracy.

Since the end of 2012, the massive mobilizations in Mexico City, including the commemorative protest of the Oct 2 massacre in Tlatelolco and Ayotzinapa protests, have been marred by the arbitrary arrest of youth and students. As social unrest has escalated in the last months with the outcry over the disappearance of the 43 rural teachers college students, police confrontation with students has also escalated.

A clear example of violence against youth linked to the increasing criminalization of social protest is the case of Jacqueline Selene Santa Lopez, a student of the Aragón School of Advanced Studies affiliated with the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Santa Lopez was detained on November 15, 2014 and falsely charged with assault and robbery of a female police officer. She was arrested, along with her boyfriend Bryan Reyes Rodriguez, also a student, in the Venustiano Carranza Delegation of Mexico City by fourteen federal police agents dressed as civilians who neither showed identification nor stated the charges against the couple.

Santa Lopez was held at the Santa Martha Acatitla women’s prison for more than eight months, all the while subjected to verbal and physical abuse. Before her detention, she was an active organizer in her school and had participated extensively in the local protests in support of the Ayotzinapa students. She was finally released this past July after a judge ruled that there was a lack of evidence to prove her guilt of the theft.

Her case is only one of hundreds in the capital and throughout the country. In 2014 there were nine cases reported by SERAPAZ and include cases in Puebla, Quintana Roo, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Mexico City and Hidalgo. In 2015 there have been at least seven reported cases in the states of Chihuahua, Puebla, Guerrero, Quintana Roo and Baja California. In the 16 cases involving more than 600 victims of violence and detentions, nine involve youth protesting against Enrique Peña Nieto and in solidarity with Ayotzinapa[1].

The most well known case is the disappearance of the 43 students of the Normal Rural Raúl Isidro Burgos teachers college in Ayotzinapa, attacked while commandeering buses to attend the Oct 2 protest in Mexico City—a massive commemorative mobilization that summons thousands of youth and students throughout the country and has nurtured student activism and solidarity for over thirty years.

Just two weeks ago, the Human Rights Commission of the Federal District (CDHDF) submitted recommendations to various local authorities for cases of criminalization of protest, arbitrary detention and attacks on journalists and human rights defenders. The report details how arrests on charges of disturbing the peace are a direct move to criminalize social protest. It also reported that many of these cases have not been investigated by the corresponding government bodies, despite evidence of torture and cruel punishment.

Ayotzinapa and Justice

For young participants and activists involved in the Ayotzinapa movement, this human rights crisis and violence directed at youth is all too present. At the March for Ayotzinapa in Mexico City last Saturday the Americas Program interviewed Pavel, a young agricultural engineer and UNAM graduate, who explained the crisis of violence youth in Mexico live today.

“I believe that the disappearance of the 43 students is a crime that should not happen in any country, in any part of the world. Currently, participating in protests against crimes of State, in this case justice for the Ayotzinapa, makes you vulnerable to falling victim to arbitrary arrest, and students in particular are a vulnerable population in protests.”

Pavel explains that “as a result of the increase in violence in the last years we’ve all realized that it can happen to any of us, not necessarily people active in movements, but anyone can be arrested. They’ll invent crimes; they’ll deny you of your liberty.”

For many young people still, this crisis serves as a motivation if not obligation to continue participating in protests. Communications student Gisela Carina Gonzales Flores explains her participation as both a protestor and young journalist.

“I find the Ayotzinapa case outrageous and sad and I think this is terrible what is happening in our country. It is something that has pulled at my heartstrings. Being a student in Mexico is more dangerous than being a drug trafficker or any type of criminal. Repression of students is very real: In a protest for Ayotzinapa on November 20 of last year a friend and I were blocked in by police. It was a terrifying experience, but it hasn’t stopped me from attending marches.”

Flashing a courageous smile behind her Nikon camera, Gisela explained, “I try to act from my own trench, from studying and not being afraid, and I work toward informing people that surround me because I think it’s the most effective way that we can enact change, both as students, and as informed and organized people.”

With cries like “It was the State!” young protestors have pointed the finger directly at Enrique Peña Nieto and his government for the disappearances of the Ayotzinapa students and for the crimes against the youth of Mexico. And according to many young people, Peña Nieto lost legitimacy as president a long time ago.

Andrea Gonzalez Aragon, from the Cuajimalpa Campus of the Autonomous Metropolitan University, states,

“I think the Mexican people are fed up with what is happening and has happened. It’s quite revealing of the inefficiency and incompetence of the government. Enrique Peña Nieto is responsible, for the simple fact of being the representative of the Mexican Republic and for having accepted that position.”

In light of the violence against youth, with the Ayotzinapa case at the center, young people like Andrea encourage Mexico to question the legitimacy of the Peña Nieto government, and tap into its courageous and resistance spirit.

“We need to look back on the Ayotzinapa case, we need to reflect. The legitimacy of this government has gone into a tailspin. We have all realized that this government is a farce,” concluded Andrea.

Notes:

[1] Control of Public Space: 3rd Report on Social Protest in Mexico, http://serapaz.org.mx/control-del-espacio-publico-tercer-informe-sobre-protesta-social-en-mexico/

Nidia Bautista is the managing director for the CIP Americas Program and writes about student protest, transborder social movements, and gender issues in Latin America.

Photos by Nicole Rothwell and Nidia Bautista