Twenty years after its implementation, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) defines the economies of Mexico, the United States and Canada, and has a too-often unrecognized effect on society as well. Most evident is the impact NAFTA has on migration.

Twenty years after its implementation, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) defines the economies of Mexico, the United States and Canada, and has a too-often unrecognized effect on society as well. Most evident is the impact NAFTA has on migration.

As supply chains are integrated, families are fractured. Governments herald the economic integration while dismissing as irrelevant the human impact. One industry – poultry production – demonstrates the social costs of “free trade,” where labor and merchandise flows unleashed by NAFTA collide to destroy lives on both sides of the border.

North Carolina’s Poultry and Migrant Booms

Following NAFTA, and in direct contradiction to its promises, migration from Mexico to the United States increased. Soon it reached upward of half a million people.

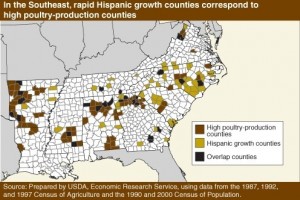

This influx of cheap Mexican labor provided the U.S. poultry industry with a competitive edge and has transformed the demographic make-up of poultry-producing counties located within states like Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia that compose what is informally known as the “southeast poultry corridor”.

What has happened in North Carolina, the second largest poultry producing state in the U.S., demonstrates the contradictions of NAFTA. On one side of the border, millions of Mexican workers were displaced, and on the other side, industries competing globally needed to keep up with rising costs, speed and demand for production opened up jobs that remained unfilled due to decreased wages.

According to the North Carolina Poultry Federation, poultry ranks as the top agricultural industry in the state. Nationally, the state ranks second in total turkey production, and third in poultry production. Poultry makes up 40 percent of North Carolina’s Total Farm Income and has an economic impact of $12.8 billion. According to the North Carolina Department of Agriculture’s International Trade Office (NCDA-ITO), North Carolina’s main poultry producers are Butterball for turkey, Case Farms for chicken, and House of Raeford for chicken and turkey. The industry supports between 68,000 and 110,000 jobs and has an estimated economic impact of $12.8 billion per year.

Poultry production in the Tar Heel State today is a far cry from the industry’s humble beginnings. In the early 20th century, raising chickens, turkeys and gathering eggs was largely women’s work, due to the little capital required to purchase and care for flocks and the small scale of operations. Increasing demand for eggs and fowl in the northern United States began to underscore poultry’s potential. As profits from cotton and tobacco crashed during the great depression and boll weevils destroyed remaining crops, enthusiasm for poultry picked up.

By 1929, the poultry industry showed how profitable it could be: the 5.8 million chickens sold off North Carolina farms brought in nearly $4.4 million, and the 240 million eggs sold reaped some $6.3 million. From 1970 to 1993, broiler, egg, and especially turkey production expanded dramatically. According to a study done by North Carolina State University, turkey production increased from 176 million pounds to 1.37 billion. Broiler production nearly tripled from 1.1 billion to 3.1 billion pounds.

Despite this historical precedent of the poultry industry taking flight, its biggest expansion came after the signing of NAFTA. In a study conducted by Business Roundtable, North Carolina’s goods exports to Mexico and Canada increased by 73 percent since 2002. By 2012, $13.1 billion of North Carolina’s goods exports, or 45 percent, went to NAFTA partners.

For poultry producers, exports took off starting in 2002. In that year, U.S. poultry producers exported $155.6 million to countries around the world. By 2004, U.S. poultry represented $192.2million out of a total $2.05 billion in worldwide poultry exports – about 10 percent.

In 1996, two years after NAFTA took effect, $6.3 million worth of North Carolina meat and poultry were exported to Mexico. By 2004, the amount more than tripled to $21.1 million. In 2012, the amount tripled once more to $65.1 million making Mexico the state’s top trade partner for meat and poultry, according to NCDA-ITO data.

As the global market for U.S. poultry expanded, so did the need for cheap labor. Although NAFTA carefully stipulated the terms for integration of industry and the flow of goods, labor was intentionally left out. Mexico became one of North Carolina’s main sources of labor for poultry production. Located at the end of the Southeastern poultry belt, North Carolina’s Latino boom is a consequence and a testament to the globalization of the poultry industry.

Migrant Path To North Carolina

The expansion of the immigrant population occurred primarily in rural rather than urban areas, in large part because of the lure of meat-and-poultry industry jobs. But the “Latinization” of North Carolina’s poultry industry did not all happen overnight. The post-NAFTA stream of Mexican migrants to North Carolina came on the heels of previous migration flows caused by economic and political changes and upheavals spanning the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

Fueled by migrations of the early 20th century and the Bracero program (1942-1964), the Mexicanization of farm labor that had taken place in the South and Southwest began moving east. Civil rights struggles increased opportunities for African Americans to work outside of agriculture creating a demand for labor.

Fueled by migrations of the early 20th century and the Bracero program (1942-1964), the Mexicanization of farm labor that had taken place in the South and Southwest began moving east. Civil rights struggles increased opportunities for African Americans to work outside of agriculture creating a demand for labor.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua spurred an influx of Central American migrants. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), passed by the U.S. Congress in 1986, caused additional migration by expanding the H2-A visa program, and allowing U.S. agricultural employers to bring in workers from Mexico and other countries through temporary visas tied to employment contracts.

The erosion of government support for agricultural production and trade liberalization in Mexico in the late 80s and accelerated under NAFTA in 1994 forced many Mexican farmers off their land and into the United States, including North Carolina. During the 1980s the state’s Hispanic population totaled 56,667, that is, 1.3 percent of the total state population. By 1990, the number reached 76,726 and by 1997, it had surged to 149,390. By 2000, Hispanic/Latinos accounted for 4.71 percent, or 378,963 of North Carolina’s population. By 2010 it had more than doubled to 800,120 or 8.39 percent, making the state’s rate of Hispanic growth the sixth fastest in the nation.

With the elimination of trade tariffs and the influx in agricultural imports from the United States, NAFTA furthered destabilization processes in the Mexican countryside. At the time of implementation, Mexico’s poultry industry – historically small-scale, local production similar to the early U.S. model – was unable to match the mechanized yields of its U.S. counterparts.

Mexican producers also had a crucial disadvantage in feed costs. Corn feed amounts to nearly 60 percent of the cost of raising a chicken. U.S. corn subsidies worth more than $10 billion annually gave U.S. poultry producers an edge that Mexican producers could not obtain. According to a piece by Peter S. Goodman for the Washington Post, labor costs could have offered Mexico a competitive edge, however labor only makes up about 5 percent of production costs.

The disruption of previously protected small-scale agriculture and depression of wages led to a surge in unauthorized migration. According to Public Citizen’s 20 year report on NAFTA’s impact, yearly migration from Mexico to the United States more than doubled from 370,000 in 1993 to 770,000 in 2000 as did the number of undocumented immigrants in the United States – from 3.9 million in 1992 to 11.1 million in 2011.

Between 1990 and 2000, North Carolina saw a 273.2 percent increase in the number of immigrants, making it the highest rate of increase in the country. Within that time span, the Latino population grew from 1.2 percent to 4.7 percent, to 8.6 percent by 2011. Small rural towns with meat and poultry as their biggest employers experienced the most change. At the heart of this demographic shift was Siler City.

Disposable Bodies, Disposable Towns

Nestled in the center of the Piedmont Valley, Siler City lies at the strained interstices of the poultry industry, trade liberalization, the fluctuations of the global market, and the flow of Latin American labor into the rural United States.

For Siler City, the simultaneous growth in the poultry industry and Latino migration came at the right moment. Surrounding textile and furniture mills had been downsizing since the 1980s. Poultry plants had been around for decades yet despite job vacancies, line jobs weren’t being filled. White and black residents weren’t applying for jobs viewed as repetitive, low-paying and dangerous. In an industry with high turnover rates and high job hazards, undocumented workers offered plants a new source of cheap and disposable labor.

Migrants legalized under IRCA had been drifting to Siler City from traditional entry points like Texas and California since the late 1980s. The steady $7-an-hour jobs and the area’s cheap housing prices offered a chance at prosperity.

By the 1990s, migration to the small southern town exploded. Companies offered incentives to workers to recruit family members or even bused them in from across the border. Once settled, the mostly male arrivals began sending for their families. By 1994, when NAFTA went into effect, migration to Siler City was already underway, but over the following six years it increased by leaps and bounds.

“I just thought, oh my God, who are these people, where are they coming from and why are they here of all places?” said Ilana Dubester, Chatham resident and founder of The Hispanic Liaison of Chatham County, one of the first direct service and Latino advocacy organizations in the state.

Dubester arrived in Chatham County in 1991 to start an organic farm with her then-husband. After settling on a 10-acre plot of land between Pittsboro and Siler City, she began driving into the post office to pick up the mail. On her trips to town, she began to notice changes.

“It was a town in distress. A lot of businesses were boarded up and there wasn’t a lot going on,” said Dubester.

Little by little, Spanish language signs and speakers turned up in the supermarket and pharmacy. The new residents were having a hard time adjusting to life in rural North Carolina. Many of them had little money and limited English or literacy skills. Dubester, a Brazilian immigrant, began taking an interest in the newcomers’ lives and figuring out how they ended up in Siler City.

In 1995 she helped found the Hispanic Liaison (El Vínculo Hispano, EVH).

In the first year, the organization had 96 clients. Three years later, the organization was helping several hundred clients access legal services and representation, and offered food and nutrition assistance. It helped file claims for legalization papers, provided driver’s education classes in Spanish, and helped bridge cultural gaps between white, African American and Latino residents. According to Dubester, the majority of clients had migrated for economic reasons and most came to work in the poultry business.

The first wave of immigrants included men who had been lured by the promise of housing and high wages. But upon arrival in Siler City, they were pointed to a local trailer park without housing subsidies. “Living conditions were meager at best, and hazardous at worst,” said Dubester. “Sometimes you had 12 guys living in a trailer sharing beds because they worked shifts. None of these trailers had heat. We would get a lot of complaints and calls from the town manager about the men eating people’s dogs that had gotten loose. For the men, alcoholism became a serious problem. But it started going down with the arrival of families.”

The arrival of wives and children in the late 90s marked the second wave of migration.

“In the early years I couldn’t understand how people ended up [in Siler City],” said Dubester, “People would say a cousin, or friend had told them about a job in the poultry plant. That was more common for the second wave of arrivals, but for the first wave, the big lure were flyers tacked up across the border by Townsend’s saying things like ‘Come to Siler City, a great place to live.’ ”

According to Dubester, workers also talked about “coyotes” being paid as intermediaries to recruit people to work at the chicken plants.

“But once you reach critical mass, you don’t need recruiting,” Dubester explained.

The small, once-dying town of 4,000 residents expanded to nearly 7,000 from 1994 to 2000. With this demographic expansion came an economic boom – new residents began snapping up real estate and opening up businesses catering to the growing Latino community.

Despite the boom, for long-time residents the transition was difficult. In August 1999, a local commissioner wrote to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service asking for help to deport undocumented workers. White and African-American parents complained about the effect immigrant children were having on classrooms and school test scores. Tensions boiled over in early April of 2000, when the Ku Klux Klan staged a rally on the steps of City Hall after a local business owner contacted notorious Klan leader David Duke to complain about the growing “Hispanic “problem.”

An article about the rally by local journalist Paul Cuadros, quotes Duke as saying “What’s going on in this country is a few companies are hiring illegal aliens and not American citizens because they can save a few bucks. I guess they need someone to pluck the chickens, but it’s not just the chickens that are getting plucked.”

Some 400 people attended the rally. Native residents continued to express anger at the changes, but as years passed, immigrant residents began to mobilize to defend their rights. Six years after the Klan rally, another demonstration took place in little Siler City. Hundreds of immigrant town members and supporters led a solidarity march and rally for immigrants rights. The event was part of over 100 rallies taking place throughout the country in response to the controversial Sensenbrenner bill, H.R. 4437, which aimed to make illegal immigration a felony and prosecute employers who hired illegal immigrants.

Many residents viewed the march as an affront, but the message was clear: The Latino community is here and not going away anytime soon.

“This is us getting together in a national movement to say we are here, and we matter. We are here, and we are human, and we have rights. And we’re not just here to break our backs and break our bones, building your houses, cutting your chicken and taking nothing back, nothing in return. This is the same as slavery,” said Dubester in an IndyWeek article.

Workers sometimes whispered about impending Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids, but raids were mostly carried out in other industries in neighboring towns. For a while it seemed that tensions had finally begun to settle.

Then, two years later, the town would face a different sort of crisis.

Recession Leads To Factory Closures

With the Great Recession of 2008, consumers tightened their belts, causing demand for chicken to plummet. The industry’s two biggest foreign markets, Russia and China, slashed orders. At the same time, fuel prices skyrocketed, increasing the cost of chicken feed as some corn crops were diverted to produce ethanol and international commodity speculation drove grain prices sky high.

The economic crisis wreaked havoc across North Carolina’s then $3.3 billion poultry industry. Export-wise, poultry saw its biggest losses between 2009 and 2010 – in 2008, it registered $420.6 million in exports. By 2009, it had dropped to $401.9 million and 2010 brought a dismal $377.2 million.

Siler City got hit hard by the recession. In 2008, the Pilgrim’s Pride-owned Gold Kist plant shut down, citing the high cost of feed and soaring fuel prices as the primary causes. The town lost 1,100 jobs. The plant closure dealt a blow to the town’s budget. Pilgrim’s Pride was one of Siler City’s biggest water and sewer customers. From the single plant closure, the town lost an estimated $1.2 million in revenue.

Three years later, chicken processor Townsends, Inc. was bought out of bankruptcy by Ukrainian billionaire Oleg Bakhmatyuk, owner of AVANGARDCO, the world’s second largest egg producer. Just five months later Bakhmatyuk, shut it down, eliminating 600 jobs. The town of Siler City ended up losing an additional $1.5 million from its water revenue. Contract farmers around the area were left with massive debts due to unserviced contracts ranging between $200,000 and $450,000.

Cutting their losses, some Hispanic workers began to call it a day.

“It was sad. When the plant shut down, you saw families lined up at the Western Union waiting for money from their families to go back to Mexico,” said Cristi Sagrera, owner of Cristi’s Hair Salon.

Today, walking through the south side of Siler City where the once-bustling Gold Kist plant stood is like walking through a parking lot. Located in the center of town, Townsends looks like a ghost plant – until recently, a fleet of trucks stood in the loading dock waiting to move crates that would never be loaded.

But even with the chickens gone, many Latino workers decided to stay. Their U.S.- born children were enrolled in local schools, and the opportunities for work still seemed more palatable than going back.

“There’s family clans that came over that live in this town now,” said Dubester., “Ffamilies have made [the population] a lot less mobile.”

Today, according to the latest U.S. Census numbers, Latinos represent over 50 percent of the town’s 8,228 residents. However, jobs continue to run scarce.

“Siler City is a dying town. We need a chicken plant to open again, something,” said Sagrera.

Work On The Line: Pain, Sexual Harassment Insecurity

“Over the years, the poultry industry has grown into a dynamic trade that shapes the local community by promoting a stronger economy, environmental responsibility and a healthier lifestyle. With increasing educational programs and advances in agricultural production technology, the industry should continue to expand and develop in North Carolina and throughout the nation,” wrote Bob Ford, executive director of the North Carolina Poultry Federation, in an article published for the March 28, 2011, edition of ‘Poultry Times.’

Many question the claim that the poultry industry promotes a healthier lifestyle.

In 2008, The Charlotte Observer ran a 22-month investigative series on poultry processing in North and South Carolina. The investigation found that the poultry industry in both states was riddled with weak regulations and enforcement that made it easy to exploit workers, most of whom were undocumented. The reports featured workers with mutilated hands and debilitating musculoskeletal disorders who had little to no protection or recourse to claim damages.

When I met Evelyn Mijangos, she was working at Cristi Sagrera’s salon in downtown Siler City. Her fresh, youthful face belied her processing experience. In her words, the transition from plucking poultry to plucking eyebrows and cutting hair had been an easy one.

“Never in my life had I worked on carving up chickens. It was incredibly fast, you would get something like 13 chickens per minute that you’d have to use a special grip on to rip off the wings and get out the bones,” said Mijangos. “I used gloves but after only a week, my hands still felt awful. The line manager would yell at us all the time too, so I spent most of my time crying.”

As she wrangled her 2-year old daughter in the warmth of her hardwood-floored kitchen, we spoke about her journey in the poultry industry. Mijangos, 34, arrived in North Carolina in 2010. After working several low-paying jobs, she and her husband left her native Guatemala in pursuit of a better life for her two boys, then aged 9 and 3. Because her brother-in-law lived in Siler City with his family of four, it made sense to her and her husband to resettle in rural North Carolina.

The new arrivals lived at her brother-in-law’s for several months. Realizing that she would need to make an income while her husband looked for work, Evelyn began working at McDonald’s. However, the low wages soon made her look for other opportunities. She applied to work at the Townsends chicken plant in Sanford and was assigned to work as a deboner.

Line work is among the most grueling. A report by the Southern Poverty Law Center states that “poultry workers often endure debilitating pain in their hands, gnarled fingers, chemical burns, and respiratory problems – tell-tale signs of repetitive motion injuries, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, and other ailments that flourish in these plants. The processing line that whisks birds through the plant moves at a punishing speed. Over three-quarters of workers said that the speed makes their work more dangerous. It is a predominant factor in the most common type of injuries, called musculoskeletal disorders.”

After several weeks of dealing with pain and the pressure of handling dozens of chickens per minute, Evelyn spoke with a supervisor and said she couldn’t keep up with the pace. She was moved around to another section of the line to work as a washer, cleaning off chickens that fell to the ground. She says her change had everything to do with her ability to stand up for herself.

“I think about other men and women who were there without papers and couldn’t say anything because they were afraid to lose their jobs,” said Evelyn, a permanent legal resident, “Those were the people who got treated the worst. They just kept increasing the speed of the chickens and making them work harder and harder.”

According to Evelyn, most of those who were undocumented would use fake Social Security numbers to get in the door. No one ever bothered to check the authenticity of the documents. Frequently, undocumented workers were encouraged to inform family members about work opportunities at the processing plant with cash bonuses, a practice that is not uncommon. In November 1996, the Los Angeles Times ran a three-part story on “The Chicken Trail.” The story looked at the recruitment of Latino poultry workers along the U.S.-Mexico border for employment in southeastern states from Arkansas and Missouri to the Carolinas.

The majority of workers are from Mexico. But Mijangos notes that immigrants from other countries have also been recruited to work in chicken processing.

“We had some Chinese workers, some Iraqi ones, Africans. They were brought in on trucks in the morning and usually worked the longest and the hardest,” said Evelyn, “I’m not sure where they came from, probably Raleigh. Some had visas but some others didn’t.”

Beyond the pain and pressure, the worst part about working at Townsends was being a woman.

“The harassment was constant. It came from co-workers, it came from the line managers, the supervisors, everyone. It was really awful and depressing, I didn’t feel like my body was mine,” said Evelyn.

While she was mostly subjected to verbal harassment, one of her fellow washers was groped by a line manager as she tried to navigate the narrow corridors between assembly lines. Being documented helped her report the line manager who was subsequently fired.

“I always thought, what would my husband say? What will he think? But I stayed because I knew the plants were closing down. I also had a home, my husband – even though he’s a citizen – had a real tough time finding a job, so I needed to support our kids,” said Evelyn.

In the past, the Delaware-based Townsends Inc. has faced several sexual harassment issues. A class action lawsuit filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in June 1998 against one of its newest acquisitions, Grace Culinary Systems in Laurel, Maryland, claimed that a number of immigrant women employees were asked by supervisors to perform sexual favors or risk losing their jobs.

Reported incidents included a rape, groping and solicitations by several managers and hourly workers. While the majority of incidents happened prior to Townsends’ acquisition of the company, harassment continued under the new management. Two years after the case was brought to court, the company reached a settlement and paid out $1 million to the 22 defendants. One month later, Townsends sold off the business.

Considering that her employer had a history with sexual harassment cases, Evelyn felt she was lucky that she was on the lighter end of the harassment being dealt out. She also felt lucky that she left after only six months.

“Sometimes, you shut yourself off to other possibilities. You talk about working at other jobs with friends but then end up going from poultry plant to poultry plant because that’s the only trade you’ve learned and you get stuck,” Evelyn said. “A friend of mine has worked in plants since she was 18. She didn’t really learn to write or read. It’s hard to find anything else or to think you can do better.”

Across towns in North Carolina, poultry workers face similar hazards and questions.

Originally from the Mexican state of Guerrero, Orlando’s parents moved from California to Warrenton, North Carolina, when they learned by word of mouth that poultry plants were offering jobs in the area. Initially, his father worked as an egg picker. A contract crew leader eventually promoted Orlando’s father to crew leader, in charge of vaccinations. Frequently, contractors employ crews for larger companies to carry out processing tasks ranging from vaccinating to moving chickens from one location to another.

Starting from the age of 13 until he turned 18, Orlando would tag along with his parents during the summer to help out with the chickens. According to Orlando, his parents wanted him to learn the value of hard work. The crews he worked with were comprised of mostly Mexican males with a few Salvadorans and Guatemalans mixed in.

“[A lot of these guys] are human beings just trying to survive. They wanted to work to sustain themselves and their families in a place that essentially makes it illegal for them to survive,” said Orlando.

“These people don’t have rights – they won’t complain that there is no soap at most of these facilities so that they can wash their hands; they won’t complain that in some of the coops, the temperature exceeds 100 degrees Fahrenheit; they don’t believe they can complain about the lack of bathroom facilities at almost all of the chicken farms; they can’t complain about the excessive dust and chicken feathers and feces that saturate these houses.”

Most of Orlando’s observations are from nearly a decade ago. While chicken houses have become better ventilated and cleaner, not all houses comply with newer standards.

“In some chicken houses, the floor, which is supposed to be covered with fresh shavings, is composed of a thick, mud-like agglomeration of feces, feathers, dirt, ammonia, and in some parts of the remains of chickens,” said Orlando.

Given that there are thousands of chickens packed into one coop, often owners and employees miss picking up the dead carcasses, which are left to rot.

In his opinion, the worst aspect of the work was the intense pain experienced by crew members from being bent over 8 to 12 hours a day picking up chickens. While he worked with his parents vaccinating chickens – a task considered less strenuous – the job had its own set of challenges.

“There were many instances when people accidently injected themselves. Usually this means that they go to the emergency room only to be sent back home because the doctors are not exactly familiar with these injuries or equipped to deal with them,” said Orlando, “On one occasion, this one guy waited to go to the doctor until the next day, which led to an infection that required surgery. On more than one occasion, workers who waited too long to go the doctor have been told that they ran the risk of losing a limb. In some cases, they were told that their injury could have been fatal.

One of his family members who worked in vaccination, ended up with a crooked finger. Orlando’s father has had problems with swollen joints. Orlando says he is still young but he worries about how the time he spent working with his parents will affect his health in the future.

“My question is always, ‘what about the future? What will these muscle and joint pains mean for any of the workers as they age? What will exposure to the dust and chemicals potentially lead to?’ ”

20 Years: A Look Back

The influx of Mexican and Central American migrants to North Carolina as a result of free trade agreements is one of the clearest signs that NAFTA and NAFTA copies like CAFTA failed to keep promises of increasing living standards and providing economic opportunities that would keep people from migrating to the United States.

The blow to workers has gone both ways. As Mexicans were forced off their land and migrated to take dangerous jobs like in the U.S. poultry sector, NAFTA also wreaked havoc in the United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, North Carolina lost 44.9 percent (358, 306) of its manufacturing jobs during the first 20 years of NAFTA. The Economic Policy Institute found that 18,900 jobs have been lost or displaced in North Carolina, and nearly 700,000 across the United States, due to an increased trade deficit with Mexico since NAFTA was implemented in 1994.

In poultry, it’s not a situation of one country winning and the other losing. Small farmers on both sides of the border have lost out under NAFTA. According to a report by the Pew Environment Group, “In 1950, more than 1.6 million farms spread across the country were growing chickens for American consumers. By 2007, fully 98 percent of those chicken farms were gone, despite the fact that Americans were consuming even more chicken – more than 85 pounds per person per year. Top firms now control the market, while smaller farms barely get by with their dwindling production earnings.”

In the meantime, demand for poultry continues to rise as do the articles extolling the virtues of NAFTA for meeting that demand. According to an article in worldpoultry.net, NAFTA “contributed to unprecedented growth in poultry production” by increasing poultry production in the United States by four-and-a-half times and doubling egg production. Export volume and value to Mexico have increased by 358 percent and 415 percent respectively. Meanwhile, Mexico’s poultry and egg production, has increased at an average annual rate of 4.3 percent and 2.8 percent, respectively and continues to work on gaining entry to the United States for its raw poultry products – thus far, Mexico has not been allowed to export raw poultry products due to the USDA’s stringent and somewhat one-sided health regulations.

With demand for poultry up and pressures to cut costs and increase efficiency high, the poultry industry seems more interested in making profits than keeping standards. Currently, the USDA is finalizing a proposal that would replace nearly 40 percent of government inspectors with company employees and speed up the factory production process from 155 birds per minute to 175 in chicken plants and from 32 birds per minute to 55 per minute in turkey plants.

Known as the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point-based Inspection Models Project (HIMP), the program was initiated in 1999 as a pilot in 25 participating plants across the country. If the proposal is approved by the USDA as a rule, the industry claims it would gain nearly $257 million in revenue each year and save $90 million over three years. An estimated 800 USDA slaughter-line inspectors would be cut from the payroll. This despite evidence that violation of the minimal existing norms is rampant.

Advocates of the rule say the proposal actually decreases food-borne illness, while decreasing industry and federal costs since inspectors would be trained to do off-line inspections to identify chickens carrying pathogens like salmonella instead of conducting quality control by looking for blemished and broken chicken carcasses. Detractors say that while rates of food-borne illnesses like salmonella seem to be decreasing, in fact the same number of people continue to get infected annually. The discrepancy in these statistics occurs because of outdated testing methods and efforts to cover up outbreaks of infection. Consumer exposure to unsafe chemicals, unsanitary particles, and worker safety are also top concerns.

“If the new rule is implemented, all chicken will be presumed to be contaminated with feces, pus, scabs, and bile and washed in a chlorine solution,” explains ChickenJustice.org. “Consumers will eat chicken with more chemical residue and contaminants. With faster production rates, workers’ injuries will increase. They will also face breathing and skin problems from constant exposure to chlorine wash. OSHA will take the next three years to study the impact of the faster processing lines on workers, but USDA wants to implement the rule immediately.”

For migrant workers displaced by NAFTA, increased line speeds will mean more injuries, more pressure, and more exposure to dangerous chemicals and pathogens.

Moreover, the U.S., Mexico and other nations move ahead on discussions on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that would establish a NAFTA-style trade agreement between the western Americas and Asia. Dubbed “NAFTA on Steroids,” TPP would further deregulate telecommunications and financial services, extend restrictive intellectual property rights laws, and increase free trade for commodities like dairy, textiles, and poultry. The future of poultry and poultry workers could be in danger under this new agreement. Similar to NAFTA, TPP would likely cause another wave of suffering for small-scale manufacturers and farmers while benefiting transnational corporations with laws and rules that would directly boost their bottom lines.

Members of the USA Poultry & Egg Export Council are calling for greater cooperation between the United States and Mexico in support of the TPP. Yet at a public hearing on the U.S. International Trade Commission’s investigation on the impact of TPP, National Chicken Council president Mike Brown complained of low sanitation standards in the Mexican poultry industry, which lead to high rates of Exotic Newcastle disease and what he called “bogus” anti-dumping cases to interrupt trade. The Mexicans complain that the U.S. industry has put up hurdles to prevent them from access to the huge U.S. market while exporting large quantities into Mexico.

In the end, workers at the tail end of TPP or HIMP negotiations could wind up with their lives and livelihoods on the line. More factory closures as companies relocate to low-cost labor alternative countries, lowered health standards and decreased worker health and safety protections seem to be the wave of the future for an industry that reflects globalization in rural towns struggling to survive.

Like Siler City, North Carolina.

Alexandra McAnarney is a communications consultant who works and lives in the Siler City area. She is a regular contributor to the CIP Americas Program www.americas.org. A native of El Salvador and former resident of Mexico City, her work focuses on migration, youth, gangs, and health and can be found at perishmotherland.tumblr.com