Editor’s Note: This week Chile finally began its second attempt at drafting and adopting a new constitution, with the installation of a group of experts designated by Congress began work on a new draft. The experts’ draft considerations will then go to the elected Constitutional Council and the plebiscite is scheduled to take place Dec. 17, 2023. This article, published in Spanish by americas.org shortly after the vote to reject the historically progressive first draft, examines the factors that led to the rejection, the mistakes of the backers of the constitution and the disinformation campaign by the right, and the challenges the nation faces to overturn the constitution imposed by the dictatorship.

Editor’s Note: This week Chile finally began its second attempt at drafting and adopting a new constitution, with the installation of a group of experts designated by Congress began work on a new draft. The experts’ draft considerations will then go to the elected Constitutional Council and the plebiscite is scheduled to take place Dec. 17, 2023. This article, published in Spanish by americas.org shortly after the vote to reject the historically progressive first draft, examines the factors that led to the rejection, the mistakes of the backers of the constitution and the disinformation campaign by the right, and the challenges the nation faces to overturn the constitution imposed by the dictatorship.

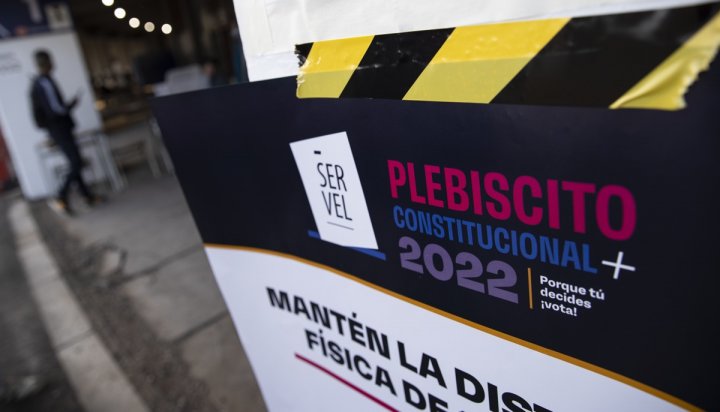

One week after the Chilean citizens overwhelmingly voted to reject the text of the new Magna Carta in the plebiscite on September 4 (62% to 38%), the leaders of the political parties in Chile, with the exception of the far-right Republican Party of Sebastián Katz, met to outline a new constitutional process. They agreed to designate a completely new body, elected by popular vote, in charge of drafting the new text, although the number of people that will integrate it is not yet known.

Unlike the previous process, its new wording would be reviewed by a committee of experts, although the format has not yet been defined. The new body will also made up of equal representation of men and women, and a plebiscite with a mandatory vote will be necessary to adopt the new version. But the definition of the rules of the new constituent process will not be easy.

The rejection was not a surprise. Since April, all the polls indicated the defeat of the new constitution, but they anticipated a maximum difference of 10 percentage points. What none of them got right was the magnitude of this difference (24 points). The vote was the last legal step established in the “Agreement for Peace and a New Constitution”, signed in November 2019, as a way out of the political crisis generated by the social uprising in October 2019, which took the lives of 38 people and left hundreds injured.

The text of the new Constitution was rejected in all the states of the country. Only 8 of the country’s 346 communes (equivalent to municipalities in other countries) approved it. The poorest 20% of the population rejected the proposal with 75% of the vote. The same thing happened in Araucanía and also in the Valparaíso Region, strongholds of President Gabriel Boric’s Broad Front, and even in prisons.

What happened?

Despite the deficiencies or excesses that the rejected text may have contained, it introduced important modifications such as the concept of democracy with parity between men and women in the conformation of all State bodies; the recognition of indigenous peoples through the introduction of the concept of plurinationality, one of the aspects most manipulated and misrepresented by the media; the change of role from a subsidiary State to a social and democratic one based on rule of law; the free exercise of sexual and reproductive rights, including State protection for voluntary termination of pregnancy; a public social security system that includes benefits for those who perform domestic and care work; the human right to water and deprivatization, among other political changes.

Many different interpretations of the widespread rejection have been proffered. What is unquestionable is that the those who sought to change the 1980 Constitution made some mistakes. The most notable was not putting enough effort into campaigning actively and effectively for the text in the vote to adopt it. Instead, they focused on the content of the text itself, in which the rightwing had little participation. Nor was there a clear message or a compelling central idea for the population. The backers of the new constitution lacked what the right had plenty of: marketing. The right also had the good sense of keeping their political liabilities– José Antonio Katz and Sebastián Piñera—in the closet.

In the end, those who sought to change the constitution could not stand up to the fierce disinformation campaign mounted by the opposition that bet all its chips on the plebiscite, basically abandoning the process of drafting the constitutional text, except to insult it through the power of the media and social networks. Messages included affirmations that the State would appropriate homes, that pension funds would not be inheritable, that the country would be divided by incorporating the concept of plurinationality, that pregnancies could be terminated a few days before the birth, deeply penetrated the population.

The pandemic was also a factor that worked against the Convention. The first referendum on changing the Constitution and how to do it, was scheduled for March 2020. However, it could not be held until October of that year, when the protests in the streets had ceased to be the central expression of popular pressure. The popular movement lost momentum.

With citizens in lockdown, debates over the articles were held at the Constituent Convention, installed in July 2021. This produced a kind of divorce between popular organizations and their representatives. This was critical in an assembly where 42% of the members corresponded to independent forces, as a result of the fact that for the first time, organizations were allowed to present lists to compete with the traditional parties on equal terms.

Another factor that played against the new constitution was the economic crisis, expressed in high levels of inflation and currency devaluation, a slowdown in growth, induced by external factors, high levels of indebtedness as a consequence of the pandemic, increased violence and crime and drug trafficking, which the uninformed population fed by the media associated with the administration of Gabriel Boric.

Turn to the center

As soon as the results were known, Boric recognized that the citizens had clearly expressed their disagreement with the text, and said that the path had to be found to develop a proposal with broad consensus to comply with the majority will to change the current constitution. He announced that a new constituent itinerary would be sought that would collect the learning from the long process of elaboration of the text and manage to interpret the citizen consensus.

As a bow to citizen sentiment, Boric made important changes in the cabinet, the first since he took office in March, by removing senior officials from his inner circle. The most important took place in Interior and Public Security, the General Secretariat of the Presidency, Social Development and Family, Health, Energy and Science and Technology.

The appointment of representatives of the Christian Democracy and the Socialist Party in some of these ministries indicated the return of the center-left, which was defeated in all the elections after the social uprisings of 2019. The defeat of the center was also evident in the election of the 155 delegates who formed the Constitutional Convention in May of 2021. On that same date, regional governors (for the first time), mayors and councilors were elected. Independents and representatives of the more radical leftist forces grouped in the Approve Dignity coalition (Broad Front, Communist Party and other minor ones) won a resounding victory.

The representatives of the right-wing parties grouped in Piñera’s official list, Vamos por Chile, got 23% of the votes, not even reaching a third of the votes, which would have given them veto power over the contents of the text of the new Constitution. Worse was the former Concertación (Socialist Party, Christian Democracy, others) that obtained only 16% of votes. In the last referendum, many of its members voted to reject it.

The weak showing of traditional parties that, with minor nuances, administered the neoliberal model inherited from the military dictatorship for the last three decades, also became evident in November 2021 during the presidential elections. The winners in the first round (Kast, with 27.9% of the validly cast votes and Boric, with 25.8%) campaigned from radical positions on the Chilean political spectrum.

What’s coming

The pre-agreement reached on September 12 in the National Congress to continue with the constituent process and evaluate the most appropriate mechanisms will face serious obstacles. Katz’s Republican Party rejects a new constituent process and considers that eventual changes to the Magna Carta should be in Congress’s hands where the opposition has a majority in the Senate. Some even consider that the Constitution of Augusto Pinochet should be maintained and invoke article 142 of the current Constitution, which establishes in its final paragraph that “If the question posed to the electorate in the ratification plebiscite is rejected, this Constitution will continue in force.” Some members consider that it is not worth changing a constitution that has led Chile to be `the best country in the region´, although that cliché contradicts the opinion of some 70% of Chileans who, according to surveys and despite the vote of rejection of the text elaborated by the Constituent Convention, want a change of Constitution.

The Chile Vamos Coalition will not make things easy either. The day after the preliminary agreement was reached, the group requested the postponement of the scheduled meetings to continue defining the details, because they had to evaluate the decisions internally. In addition, they demanded that the government exclude itself from the dialogue, since they felt that it was giving orders. This request to exclude the government from the talks was the response to the impertinent statements by Boric’s spokeswoman, Camila Vallejo, when she stated that the government had already outlined its path for the constitutional process, when there were still aspects that had not been defined. This impasse caused some deputies to move to the the position of some Republican Party representatives who proposed a new plebiscite to ask the public whether they wanted a new constitution or not.

The new constituent process faces an opposition that has emerged strengthened with the result of the plebiscite, in a scenario in which the popular fervor in the streets has vanished, and the economic scenario is increasingly adverse. Many of the advances of the rejected constitutional text will be seriously limited or rolled back. But in historical perspective it is still a victory. Citizens will have a Constitution written in democracy and not by a military junta.

Originally published in Spanish on September 30, 2022: https://www.americas.org/es/chile-que-viene-despues-del-rechazo/

Ariela Ruiz Caro is an economist with a master’s degree in economic integration processes from the University of Buenos Aires, and an international adviser for the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Latin American Economic System (SELA) and the Institute for the Integration of Latin America and the Caribbean (INTAL). She has been an official with the Andean Community, an adviser to MERCOSUR’s Commission of Permanent Representatives, and the Economic Attaché of the Peruvian Embassy in Argentina. She serves as the Americas Program analyst for the Andean/Southern Cone region.

Ariela Ruiz Caro is an economist with a master’s degree in economic integration processes from the University of Buenos Aires, and an international adviser for the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Latin American Economic System (SELA) and the Institute for the Integration of Latin America and the Caribbean (INTAL). She has been an official with the Andean Community, an adviser to MERCOSUR’s Commission of Permanent Representatives, and the Economic Attaché of the Peruvian Embassy in Argentina. She serves as the Americas Program analyst for the Andean/Southern Cone region.