El mundo en foco | Columna de análisis

As Donald Trump’s administration takes blatant interventionist stance in our region, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Claudio Castro, a member of Jair Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party, ordered a joint operation by the 2,500 officers of the Civil and Military Police to capture members of the Comando Vermelho, one of the country’s main drug gangs.

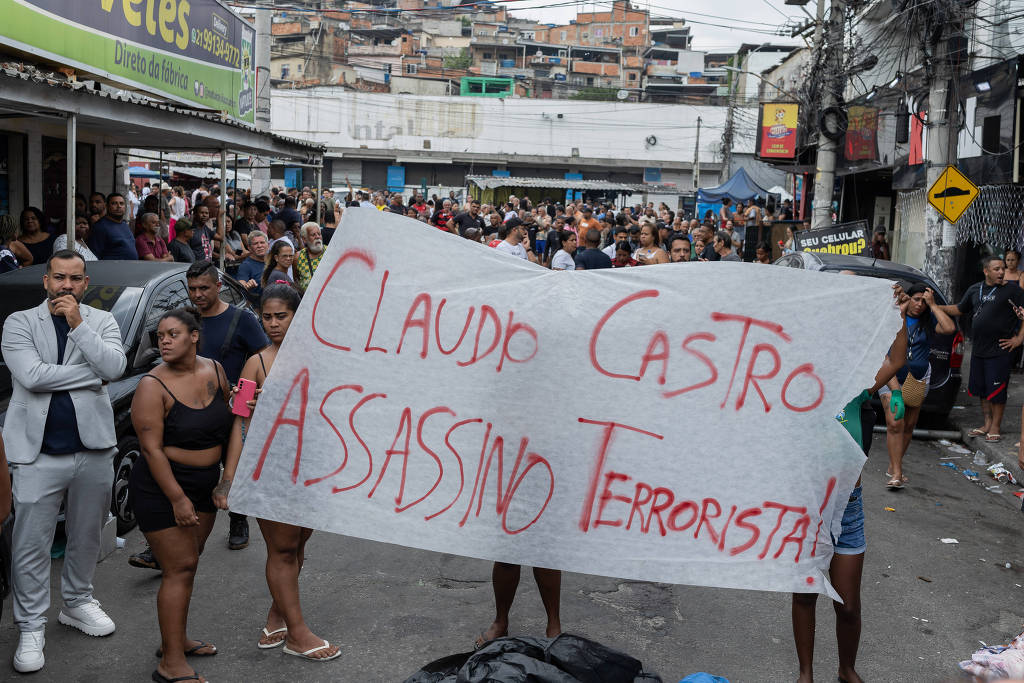

“Operation Containment” launched on Oct. 28, under the exclusive responsibility of the state of Rio de Janeiro and without the knowledge of the federal government, in two favelas located in the north of the city. It left more than 130 people dead, including four police officers, and 113 detained, making it the deadliest operation in the country’s recent history. The massacre has been condemned by the United Nations Human Rights Organization, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), Human Rights Watch, among others.

Human rights organizations immediately condemned the raids. The UN Office for Human Rights said it was “horrified” by the operation. “We remind the authorities of their obligations under international law and urge them to conduct prompt and effective investigations” into the deaths, said the office headed by High Commissioner Volker Türk. Human Rights Watch (HRW) Brazil described the police operation as a “disaster” and called on the prosecutor’s office to investigate the circumstances of each death. “A police operation that results in the deaths of more than 60 residents and police officers is an enormous tragedy,” said director César Muñoz. All agree in strongly condemning the raid.

The IACHR, the autonomous human rights body of the Organizaton of American States, issued a statement on Oct. 31, urging the State to investigate the events promptly, diligently, and independently, taking into account the entire chain of command, to punish those responsible, and to guarantee comprehensive reparations to the victims and their families. The IACHR observed that the joint operation is part of a persistent pattern of police violence in Rio de Janeiro, more than 85% of whose victims are people of African descent and that the data show a pattern of racial profiling and reflect the continuation of a security model focused on the excessive use of force and the criminalization of poverty. The IACHR recognized the seriousness of the scourge of organized crime and its impact on the effective enjoyment of human rights, however, it expressed concern about the persistence of the “war on crime” paradigm, which dehumanizes victims and has proven ineffective as a public security strategy for reducing levels of violence. In this context. The body urged Brazilian authorities, including those at the state level, to reformulate their policies against organized crime with a human rights-based, victim-centered approach and social participation, in accordance with inter-American standards.

Colombian Gustavo Petro is the only president in the region who has criticized the governor of Rio de Janeiro, describing the police operation in the favelas as “barbaric.”

“The pain of the poor. Barbarism is the common denominator of the extreme right,” Petro wrote in X, comparing the operation to the worst period of paramilitarism in Colombia, whose alliances with the army left a trail of blood.

The Trump-Bolsonaro alliance

Governor Claudio Castro did not inform or coordinate the actions with the federal government, but he did have time to send the US government, months earlier, a report on the Comando Vermelho, which he described as a terrorist organization with active ramifications in the United States. According to CNN, the report was delivered directly to the US consulate in Rio. The aim of informing Washington was to establish himself as a partner and champion of cooperation with U.S. authorities in the fight against the faction. By promoting the classification of these criminal groups as terrorists, the Bolsonaristas align themselves with U.S. policy, opening the door to U.S. intervention in Brazil for alleged reasons of national security. Given the prevailing fear in Brazilian society, who better than the United States to protect it?

It’s all part of the strategy for the October 2026 presidential election campaign in Brazil. In May, a commission of Brazilian lawmakers held a meeting with representatives of the US embassy to ask the US government to declare the drug gangs Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), the largest in Brazil, and Comando Vermelho as terrorists. Senator Flavio Bolsonaro, Jair’s youngest son, and Congressman Paulo Bilynskyj, the leaders of the Public Security committees of the legislative chambers, attended. Flavio Bolsonaro also asked President Lula’s government to “embrace” the initiative and “formalize” any agreement that may be reached with the United States. According to SwissInfo, the legislators asked the embassy to coordinate a meeting in Washington between the U.S. government and public security officials from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo to present them with an intelligence report linking the PCC and Comando Vermelho to the Lebanese militia Hezbollah, which Washington considers a terrorist organization. According to Bolsonaro, the report also shows that the “tentacles” of the two main Brazilian gangs reach the United States.

Days before the recent operation in Rio de Janeiro, Senator Flávio Bolsonaro also asked US authorities to expand to Brazil the illegal military campaign that the White House is conducting off the coasts of Venezuela and Colombia against small boats that allegedly transport drugs and threaten the internal security of that country. The names of the murdered crew members are not even known. Nor is there any evidence that they were transporting drugs. They simply died in a bombing at sea. The resignation of Admiral Alvin Holsey, head of the Southern Command is attributed to the opacity of these acts.

According to the UN High Commissioner, the killings in the Caribbean, and more recently in the Pacific, are “extrajudicial executions,” illegal under national and international law. As of October 30, 15 boats have been destroyed, killing 61 people, which is creating a growing crisis in the Caribbean and, more recently, also in the Pacific.

But Senator Bolsonaro thinks that’s fantastic. On Oct. 3, he posted a message from U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth on social media about the most recent attack on these vessels and wrote in English: “How envious! I hear there are ships like this in Rio de Janeiro, in Guanabara Bay, flooding Brazil with drugs. Don’t you want to spend a few months here and help us fight these terrorist organizations?” Asking President Trump to intervene in Brazil on the pretext that alleged drug boats threaten national security is music to the ears of someone who aspires to be the emperor of the world. Arrogance and flattery are two sides of the same coin.

Flavio’s post came as Brazilian diplomats worked to finalize the first bilateral meeting between President Lula and Donald Trump, which took place on Sunday, October 26, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, as part of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit. One of the objectives was to get the United States to eliminate the 50% tariffs imposed on exports from Brazil. These were announced in retaliation for the legal proceedings against Jair Bolsonaro at the end of the BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro on July 6 and 7, in which Lula played a leading role. Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, another of the former president’s sons currently based in Texas, publicly promoted sanctions against Brazil for putting his father on trial. Against all odds, and despite pressure and blackmail from Trump, Bolsonaro was sentenced on Sept. 11 to 27 years in prison for attempted coup, violent abolition of the democratic rule of law, and as a member of an armed criminal organization dedicated to discrediting the electoral system. He was also convicted of inciting attacks on democratic institutions and leading a “criminal organization” that conspired to try to prevent the current president from succeeding him after winning the October 2022 elections.

Clash of opinions

The massacre in the Rio de Janeiro favelas prompted Judge Alexandre de Moraes to summon Governor Claudio Castro to provide explanations on Nov. 3. Castro claims that the federal government failed to support them. This is absolutely false. In Brazil, states have autonomy in all areas of management, including public security. Only when a state declares itself unable to meet a challenge with its own resources does it formally request assistance from the federal government. When this occurs, in the case of public security, the federal government enacts an emergency law called the Guarantee of Law and Order (GLO). The governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro never requested the GLO. If he had, federal forces, including the Federal Police and the Armed Forces, would have taken over public security, and local forces would have been subordinated to the military authority appointed by the President of the Republic.

Lula’s government introduced a Proposed Constitutional Amendment at the beginning of the year that provides for coordinated action by all federated entities under the supervision of the Ministry of Justice (Federal Government) for a centralized structure of information and actions against organized crime. Citing crime as “the greatest risk to our institutions, the rule of law, and democracy itself” the proposal would facilitate cooperation but right-wing political forces have so far rejected it, arguing that it would diminish the autonomy of the states.

The Oct. 28 massacre has accelerated the right wing’s push for an iron hand approach in Brazil and classification of the Comando Vermelho and the PCC as “terrorist organizations.” In Paraguay, the permanent secretary of the National Defense Council, Rear Admiral Cíbar Benítez, along with the ministers of the Interior, Enrique Riera, and Defense, Óscar González, and the commanders of the Armed Forces and the National Police, have already announced that they will designate the two organizations as terrorist groups through a decree.

Meanwhile, the Human Rights Commission of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies has sent Attorney General Paulo Gonet a formal request to open an investigation and consider preventive detention of Governor Castro for the police operation in the favelas. In the document, the nine signatory deputies indicate that there is “overwhelming evidence of having exceeded the limits of the law, proportionality, and respect for human rights.”

The narrative used to justify U.S. interference in countries in the region has replaced the danger of communism with that of narcoterrorism, without mentioning, of course, that the U.S. is the largest consumer of drugs and is only concerned with eradicating it on the supply side.

Recent events indicate that as the start of the election campaign approaches, Lula will be accused of weakness in combating drug trafficking and could even be charged with being a leader of the Comando Vermelho. This comes as no surprise. The Trump government consistently goes after leaders who maintain sovereign positions. For the submissive, there is aid, support, and even applause, as seen in recent weeks in the case of Argentine President Javier Milei. Neither the corruption scandal regarding commissions his sister Karina charged elected and public officials for interviews with her brother, nor the bribery scheme in the state purchase of medicines by the National Agency for Persons with Disabilities also organized by Karina Milei, nor the cryptocurrency scams sponsored by President Milei that also drew in U.S. citizens, nor the links to drug trafficking of officials very close to Milei’s government matter if those in power belong to the U.S. choir.

“The World in Focus” is Ariela Ruiz Caro’s biweekly column for Mira: Feminisms and Democracies. Ariela Ruiz Caro is an economist with a master’s degree in economic integration processes and an international consultant on trade, integration, and natural resources at ECLAC, the Latin American Economic System (SELA), and the Institute for the Integration of Latin America and the Caribbean (INTAL), among others. She has served as an official of the Andean Community, advisor to the Commission of Permanent Representatives of MERCOSUR, and Economic Attaché at the Embassy of Peru in Argentina.