The World in Focus | Analysis column

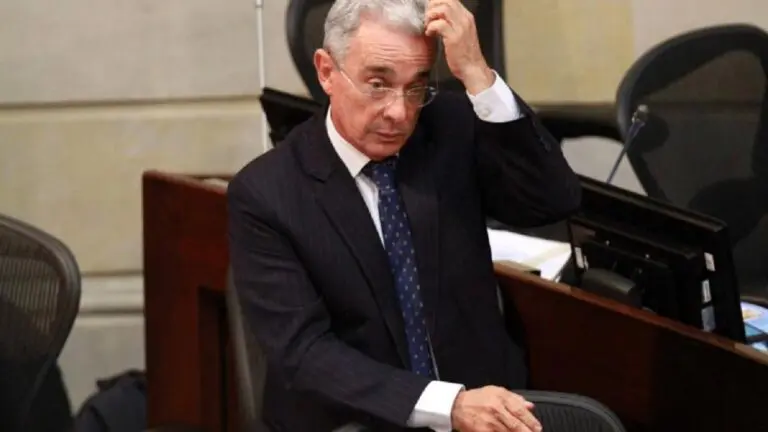

The US government’s interference in the administration of justice in countries such as Brazil and Argentina has spread to Colombia. On July 28, former President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) was found guilty in the first instance of procedural fraud and bribery in criminal proceedings by Judge Sandra Heredia. The judge based her decision on extensive evidence that Uribe’s lawyer, Diego Cadena, had been in contact with former paramilitary Juan Guillermo Monsalve, who is being held in a Bogotá prison, to prevent him from linking the former president to the paramilitaries, for which he had to retract previous statements.

U.S. authorities immediately condemned the ruling, which has become common practice when the defendants are their allies. On July 9, Donald Trump threatened 50% tariffs on Brazilian exports, linking punitive tariffs to the ongoing trial against former president Jair Bolsonaro, which he described as a “witch hunt that must end immediately”. Despite Lula’s willingness to negotiate, on July 31, Trump signed an executive order making the tariffs official, although he exempted some items.

Invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), he described Brazil as “an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.” The order also states that “the judicial proceedings against former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and his supporters constitute serious human rights abuses that have undermined the rule of law in Brazil.” This supposedly provides the legal basis for imposing unilateral sanctions such as tariffs.

In another case of open partisanship, in Argentina Trump’s ambassador-designate, Peter Lamelas, testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he would not only support Milei’s presidency during the midterm elections and his reelection, but would also ensure that former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner stands trial, after accusing her of covering up the AMIA terrorist attack. He complained that she was granted house arrest after being convicted on a fraud charge “due to certain political favoritism that exists there”.

Colombian Background

Uribe was sentenced to 12 years of house arrest on Aug. 1. At the hearing, the former president presented his appeal and, as expected, not only declared himself innocent, but also said that the decision was politically motivated and not based on legal grounds. He accused powerful politicians, including Gustavo Petro and Iván Cepeda, of being involved in the events. This is the first time a president has been convicted in Colombia.

Former President Uribe’s denounced Senator Iván Cepeda before the Supreme Court of Justice for alleged witness tampering after Cepeda claimed that the former president had links to paramilitary groups responsible for thousands of civilian deaths during the armed conflict. But his plan to discredit Cepeda backfired in 2012.

Judge José Luis Barceló accepted Uribe’s complaint, but found no evidence to support the charge. In 2018, the Court not only determined that there was no evidence of a crime on the part of Cepeda, but ordered an investigation into the former president for sending emissaries to manipulate witnesses in his favor and against the senator. In August 2020, Uribe had to resign from the Senate seat he held since 2014 and was placed under house arrest by order of the Supreme Court. The case was transferred to the ordinary courts and, five years later, Uribe was convicted on Friday in a historic verdict for Colombia.

As president, Uribe presided over the scandal surrounding “false positives”. Between 2002 and 2008, the military killed 6,400 innocent civilians whom they illegitimately presented as guerrillas killed in combat, in exchange for prizes and rewards under the so-called “democratic security” policy promoted by Álvaro Uribe. In April 2020, the first hearing was held by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, a court created as part of the 2016 Peace Agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). During the hearing, an army general, nine other military officials, and a civilian admitted to committing war crimes and crimes against humanity and presenting them as combat with rebels.

The officers said they had participated in a deliberate strategy in which they recruited ordinary Colombians, many of them students and poor farmers, most between the ages of 25 and 35, with the promise of jobs. They then killed them and reported their deaths as guerrillas killed in combat. At the hearing, Néstor Guillermo Restrepo, a former army corporal, said: “I want the world to know that they were peasants, that I, as a member of the security forces, cowardly murdered them, robbed their children of their dreams, tore their mothers’ hearts apart because of pressure, because of results, because of false results, to keep a government happy. It is not fair.“

Uribe denies any connection to the crimes, claiming they are ”isolated cases”. He has also denied that the army carried out systematic action against civilians during his term in office, an assertion that the victims’ families consider false. Now the investigation is centered on establishing who gave the orders in the chain of command. The current investigation by Judge Sandra Heredia did not seek to determine former President Uribe’s responsibility for this crime, but rather to investigate him for bribery in criminal proceedings and procedural fraud.

It is clear that Uribe is no stranger to paramilitary activities, but he is not the only one. In March 2020, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights, Michel Forst, said that despite the 2016 peace agreements, Colombia remained “the country with the highest number of human rights defenders killed in Latin America, and threats against them had skyrocketed in a context of high levels of impunity.”

In the report, Forst noted that “human rights defenders are killed and abused for implementing peace; opposing the interests of organized crime, illegal economies, corruption, and illicit land tenure; and for protecting their communities. Women defenders are also subject to gender-specific violations, and their families are also targeted.“ He also warned that ”when killings and other human rights violations are committed against defenders and remain unpunished, it sends a message of lack of recognition of their important work in society, and this implies an invitation to continue violating their rights.”

Forst pointed out that the Colombian government, under former president Iván Duque, an Uribe follower, did not allow him to enter the country to complete the report he presented at that time to the Human Rights Council.

In January 2020, allegations also emerged linking Urbe to Mexican drug cartels and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in a conspiracy to traffic large quantities of cocaine to Mexico between 2006 and 2008. If true, some analysts believe that the allegations would represent the latest in a series of incidents and revelations exposing the so-called “war on drugs” waged by the United States and Colombia as a false pretext to justify decades of militarization.

The U.S. Government’s Reaction

The first to condemn the Colombian justice system for the ruling against Álvaro Uribe was U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio. On his Twitter account, he stated that “the only crime of former Colombian President Uribe has been to fight tirelessly and defend his homeland. The manipulation of the Colombian judiciary by radical judges has set a worrying precedent.”

Immediately afterwards, Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau also weighed in on the ruling, blatantly claiming that justice had been tarnished in Colombia by the sentence against Uribe and denouncing what he called the “manipulation” of judicial systems to attack political opponents. He disparaged the Colombian justice system stating: “Our political differences should be resolved at the ballot box, not in the courts,” implying impartiality on the part of the Colombian justice system, and called for an appeal to put an end to “this procedural and judicial abuse.”

Republican senators of Colombian origin who support Trump, Rubén Gallego and Bernie Moreno, announced plans to travel to Colombia for a “have a face-to-face meeting” with President Petro and to monitor the development of democracy and guarantee the presidential elections in May next year. Republican Senator Rick Scott said that Álvaro Uribe is the victim of judicial persecution as a result of the policies implemented by Petro, whom he described as a criminal and an extremist. He urged the United States government and the international community to support Uribe and the “fight for freedom and democracy”. Republican Congressman Mario Díaz-Balart described the court’s decision as a “witch hunt” motivated by left-wing political ideology rather than a judicial review of the evidence.

Until Gustavo Petro’s victory in 2022, Colombia was the United States’ closest ally in the region. In 2009, Uribe authorized the installation of seven military bases on Colombian territory and Colombia was the first Latin American country to become a global partner of NATO in 2018. On May 23, 2022, six days before the first round of presidential elections, former President Biden officially declared Colombia a major non-NATO ally, allowing the country access to U.S. military equipment and loans for research equipment and materials. It would also have privileges in space technology procurement and could participate in cooperative projects with the US Department of Defense.

Colombia’s response

Following the statements by Rubio and Landau, Colombia’s Supreme Court of Justice (CSJ) issued a statement supporting the actions of Judge Sandra Heredia, similar to that issued by Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court in support of Judge Alexandre de Moraes, who presided over the trial of former President Jair Bolsonaro on charges of attempted coup, violent abolition of the democratic rule of law, and criminal organization.

In it, the CSJ rejected undue interference and expressions suggesting that the decisions taken by judges do not comply with the provisions of the legal system. It stated that “such statements not only erode public credibility and confidence in the justice system, but can also endanger the lives and integrity of the judges and magistrates responsible for resolving cases.”

The judges also called on political and opinion leaders, and society in general, to weigh their statements carefully, and on the parties directly involved in the proceedings to express their disagreements within the framework of due process, guaranteeing respect for judicial autonomy and independence.

President Gustavo Petro said that the U.S. position seriously affects the autonomy of the Colombian judiciary, and asked the U.S. Embassy in Colombia “not to interfere in the justice of my country.” He added that “dozens of judges, magistrates, and prosecutors have been killed in their fight against drug trafficking and the links between drug trafficking and the Colombian state.”

Colombian justice still has a long way to go. Uribe’s defense will appeal and the case could reach the Supreme Court. The United States, in alliance with sectors of the Colombian right, will continue to interfere in the justice system, especially because these events are taking place in an electoral context.

“The World in Focus” is Ariela Ruiz Caro’s biweekly column for Mira: Feminisms and Democracies. Ariela Ruiz Caro is an economist with a master’s degree in economic integration processes and an international consultant on trade, integration, and natural resources at ECLAC, the Latin American Economic System (SELA), and the Institute for the Integration of Latin America and the Caribbean (INTAL), among others. She has served as an official of the Andean Community, advisor to the Commission of Permanent Representatives of MERCOSUR, and Economic Attaché at the Embassy of Peru in Argentina.