On August 31, 2018, Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales, a comedian by profession, accompanied by his cabinet and the high command of the army, convened a press conference where he unilaterally announced that he would not renew the mandate of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). He declared that as of September 3, 2019 the CICIG, established by an agreement between the government of Guatemala and the United Nations in 2006. would completely cease functions.

On August 31, 2018, Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales, a comedian by profession, accompanied by his cabinet and the high command of the army, convened a press conference where he unilaterally announced that he would not renew the mandate of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). He declared that as of September 3, 2019 the CICIG, established by an agreement between the government of Guatemala and the United Nations in 2006. would completely cease functions.

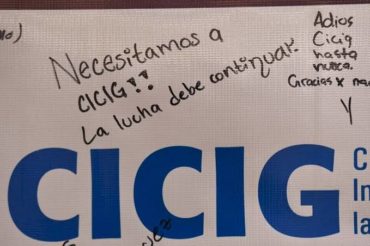

The CICIG fulfilled its mandate to end impunity and dismantle illegal security forces and clandestine devices, but despite international support and the endorsement of the United Nations Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, the Commission could not stand against the power of the Guatemalan millionaire elite. Last September, it was forced to finish his work after 12 years. However, the CICIG left an invaluable legacy of in-depth investigations, which working with the Public Ministry allowed it to take a sizable number of formerly untouchables to court.

Its work also showed that the unequal situation of approximately nine million Guatemalans who are struggling in poverty and extreme poverty is a consequence of the co-optation of the Guatemalan state by legal and illegal political-economic elites that have become an institution and reduced the country to a bounty for its own enrichment. President Morales himself was investigated by CICIG and charged with illicit financing during his campaign, while his son and brother were taken to court for fraud.

This takeover of all three branches of government—the executive, legislative and judicial—by political and economic elites of Guatemala has also occurred in neighboring countries. This explains why the signing of peace agreements in Central American in the 1990s, contrary to expectations, brought about the beginning of a mass exodus of people of all ages, especially from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

That silent exodus that nobody wanted to notice, has resulted in the current humanitarian crisis on the border between Mexico and the United States that came to public attention with the caravans that began in October 2018, when thousands of women, teenagers, boys and girls they left their places of origin to try to reach– by any means possible– the United States.

On the one hand, the Central American countries have culturally diverse populations and a wealth of water, mineral and natural resources, but on the other hand, they are countries where widespread corruption and impunity have taken root. An alliance between traditional capital and emerging capital, increasingly represented in different aspects of organized crime, make life unsustainable for families and young people who decide not to ally or work for them.

These are also countries characterized by an excessive concentration of wealth. In Guatemala in 2010, 10% of the population obtained 43.4% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while the poorest 20% survived with 2.9%. By 2014, the top 10% of the population came to concentrate 45% of the wealth. An Oxfam report from 2016 indicates that only 260 people concentrate 30 billion dollars.

The figures show the increase in the concentration of wealth among about 14 family corporations, making Guatemala one of the most unequal countries n the world, only surpassed by African countries. This reality has forced the poor majorities to emigrate, although simultaneously the best professionals also flee as soon as they can leave Central America.

In Guatemala, the old and new elites fed off the national budget This became the main booty, which ended up being controlled by small sectors that excluded the majority and exacerbated poverty and extreme poverty, especially for indigenous peoples.

The National Institute of Statistics (INE) reported in December 2015, that poverty increased 8.1 percentage points, reaching 59.3% in relation to the data obtained in 2006, and national extreme poverty increased from 15.3% in 2006 to 23.4% in 2014. National poverty is currently estimated to affect 9.6 million Guatemalans out of a total of 16 million–about 60% of the total national population is poor, of which 3.7 million live in extreme poverty. General poverty reached its highest peak in 15 years by 2016.

CICIG and the fight against corruption

The impact of corruption was to destroy lives, institutions and slowly devour the country. Given this, it was not surprising that the Guatemalan public of different social conditions was outraged when on April 16, 2015, the CICIG revealed a multi-million dollar tax fraud, headed by the Private Secretary of the Vice President of the Republic, Juan Carlos Monzón. After months of hard work, the investigation led to accusations against President Otto Pérez Molina (2012-2015) and Vice President Roxana Baldetti, who resigned to face trials.

And so the CICIG, in attacking an impunity rate exceeding 97 percent, went from being an unknown entity in terms of its functions to one of the most respected institutions.

As of 2013, CICIG, under the leadership of the Colombian jurist Iván Velásquez Gómez, had the responsibility of revealing more than 60 complex criminal networks operating in Guatemala. Further revelatons in 2016 could not have been more inopportune for the government and timely for the citizens, since the CICIG was about to be canceled as its mandate expired in September of that year. The Pérez and Baldetti government had been explicit in stating that it would not renew the mandate, while minimizing the achievements of the Commission. Exposure of the existence and form of operation of the customs fraud ring led by the executive branch under Pérez Molina, was the catalyst for various sectors to stand up and protest peacefully and massively in 2015. To this day it is not known exactly how much was stolen by the Pérez Molina administrations, previous governments and the current administration of Jimmy Morales, who finally cut off the CICIG’s mandate.

Pérez and Baldetti’s theft scandal created massive outrage in Guatemalan society, which allowed the public, from April to September 2015, to overcome class divisions and tensions with respect to the complex ethnic relations between the indigenous population and the urban Ladino populations. Mass mobilizations with some indigenous authorities, representatives of organizations, grassroots leaders, local officials and communities briefly participated together after learning about the corruption structures led by Pérez and Baldetti.

The demonstrations demanded the resignation of the Vice President of the Republic, Baldetti, which was achieved two weeks after the mobilization began, on May 8. Later, several members of the government cabinet began to resign or were removed because they were cited in the corruption investigations. President Otto Pérez held on to his position for almost four months, but hanging on a thread, supported by the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial and Financial Associations, CACIF, and the United States Embassy. Finally, given the serious accusations generated by the investigations, Pérez left power on September 2, 2015.

History of corruption

In Guatemala, the scandalous corruption dates back to the colonial era (1524-1821), but the contemorary phase began with the government of Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes (1958-1963). During this period, corruption flourished and was backed by acts of terror executed during the armed conflict, especially those of the late 1970s and early 1980s that had the effect that the regimes expected. For example, on May 21, 1981, Arturo Soto Avendaño, a professor of medicine, was kidnapped when he was going to the place where his father had allegedly suffered a traffic accident. Three days later, his body was left at the entrance of the university, with signs of torture and five bullets to the head.

More than 150 students and professors of the University of San Carlos de Guatemala were murdered. Historians report that hours before the murder of Soto Avendaño, the dean received letters from more than 50 professors, resigning or requesting leave. Almost 30% of the teaching staff retired in fear, days later the dean himself resigned.

The murder of two generations of women and men, leaders, intellectuals, professors, politicians prepared the stage for the spread of networks of corruption that through abuse of power, bribes and manipulation, took power over the public university and the rest of the institutions of the Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches. They corrupted the unions, which in the bloodiest era were persecuted, but which after the signing of the peace (1996) became negotiators and operators. That is, the political and institutional system was built around corrupt schemes embedded in expressions of daily life that affected all peoples, social classes and geographical spaces of country.

In Guatemala, it is no secret to anyone that to be treated at any public institution, you have to pay or have contacts that can grant access to care. For example, to receive emergency health care or to obtain one of the mere 200 beds in any of the seven specialized hospitals in the country (four in the capital, one in Quetzaltenango, one in Sacatepéquez and one in Izabal), regardless of your condition, you must know someone who works inside to receive state medical services, otherwise you die in the hallways. To access any service in the municipalities of the major cities, it is necessary to bribe the people in charge of the different areas if you want the procedure carried out normally, otherwise, you have to wait between 12 to 18 months for the request to be addressed.

Similarly, to apply for a position in any of the 14 ministries of the State or in Congress, it is not necessary to show technical capacity or credentials, and much less experience in the area. One case is the contracts under lines 029 and 022 of the Congress on temporary employees, where the former official party deputy and former president of the Congress (2012-2013), Gudy Rivera Estrada, controlled had 24 posts, including seven assistents with salaries of an average of $ 1,500.00 per month , several of whom never showed up for work.

To get a job in Guatemala what is required is affiliation with the political party in government, or in any case high-level contacts ranging from access to district deputies to the departmental governor. This way you can get a position, but you must be willing to give between ten and twenty percent of your monthly salary to the party or the politician who gave you the post. Given this, most bureaucrats get positions they know little about. In part, this policy of sale and purchase of positions is what has caused the inefficiency of the State of Guatemala. Women of any age, but especially young women, are often harassed and pressured to yield sexual favors in exchange for employment.

Since the last century, the Congress of the Republic became the main manager of jobs throughout the republic. These corruption processes have strengthened national and regional cacicazgos, who temporarily endorse deputies, who rise to become public servants with more national power. The system facilitates misery and corruption. In the departments, it became common to see rows of people outside the homes or offices of government officials with a resume in hand and a copy of their party affiliation, to apply for employment for themselves or their family members. The demand for jobs became so high that some deputies placed signs in their residences asking that all requests for posts be made directly in the corresponding departmental offices and no longer through them. If the public posts assigned from 1986– the beginning of the “democratic era”– to present were reviewed, the data would show the percentage of positions that were hadned out by political affiliation and not by technical or professional capacity .

Guatemalan deputies have long neglected the responsibility of legislating for the population and have also become the main construction managers in the interior of the country. To take advantage of any opportunity to get richer, they created their own NGOs managed by family or friends, creating new national and local elites around the profits generated by construction companies whose objective has been to enrich themselves in the shortest possible time with public funds, regardless of the quality or usefulness of the projects. It is normal to see that more and more the main roads of the country deteriorate, and lack controls or minimum studies in dangerous areas where a week doesn’t go by without an accident and losses of human lives.

For Indigenous Peoples, the urban and Ladino state influences their lives and determines policies that affect their lives daily, forcing the rural poor, especially children and adolescents, to abandon their lands and choose to try to reach the U.S. Although this could mean losing one’s life in the attempt, if they no longer have hope in their places of origin, it is still worth losing their lives to reach a different life.

As a result of the corruption and fragmentation promoted by political parties, transnational corporations, churches, the private sector and the State itself, at the time of the fall of Perez and Baldetti, indigenous peoples, the Ladino, mestizo and Guatemalans in general did not have a consolidated national leadership prepared to articulate, negotiate and combine their complex rural and national demands in favor of a new national project, for the defense of their lives, lands and territories.Therefore, the government led by Morales and his cabinet followed Pérez Molina. From the time it took office in 2016 until September 2019, the Morales administration dedicated itself to dismantling the CICIG. Morales and the traditional and emerging elites created a “pact of corruption” in September 2017 alongside executive, legislative and judicial officials, and members of elites, politicians and operators. This group reached out to Washington and the European Parliament, where they lobbied to allow the withdrawal of CICIG’s financial support and mandate in September 2019. Despite the support of the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, the CICIG could not be sustained because Morales, along with the national elites, made an aagreement with the President of the United States, Donald Trump, in exchange for supporting decisions that would benefit Trump, such as the transfer of the Israeli Embassy to Jerusalem, and making Guatemala a Safe Third Country to imprison Central Americans, among other measures.As Elisenda Calvet indicates in a CICIG analysis, the day Morales announced the non-renewal of the CICIG mandate, he received a call from Mike Pompeo, US Secretary of State “expressing his support for the Guatemalan government”. The call shows that there were non-public negotiations between both governments and presidents Trump and Morales to dismantle the CICIG. If it had been the other way around, if the US had supported CICIG, it would still be operating.

With the end of the CICIG, honest women and men lose, public workers who do their jobs lose, politicians and officials who worked to build another country lose, entrepreneurs who invest and carry out their responsibilities lose, small and medium investors who do not give up even though they can’t compete with corrupt monopolies lose, students and farmworkers lose. The CICIG was a historic opportunity, backed by 70% of the population of Guatemala, to make a revolution, without violence, and it will be remembered as the October Revolution of 1944 is commemorated today. The work of the CICIG Commissioner, Iván Velásquez (2013-2019), and of the prosecutors of the Public Ministry Claudia Paz y Paz (2010-2014) and Thelma Aldana (2014-2018) will remain an exemplary role model.

The CICIG taught Central America and the world that there are no untouchables in any sector, and that economic and political networks – lawful and illegal – are really responsible for the poverty, extreme poverty and unstoppable migration that Guatemala faces today.