International Women’s Day 2023 was a day of “women in all forms”, of youth, of diversities, of tens of thousands of women marching in the streets of Mexico City. From the Plaza of Women Who Struggle, where the statue of Columbus was torn down and women have claimed a monument to their movement’s leaders, to the central Plaza of the Constitution, where police guarded government buildings, the all-women march exuded joy and pain, anger and courage .

International Women’s Day 2023 was a day of “women in all forms”, of youth, of diversities, of tens of thousands of women marching in the streets of Mexico City. From the Plaza of Women Who Struggle, where the statue of Columbus was torn down and women have claimed a monument to their movement’s leaders, to the central Plaza of the Constitution, where police guarded government buildings, the all-women march exuded joy and pain, anger and courage .

With official estimates at nearly 100,000 and organizers asserting closer to 200,000, the demonstrators packed the city’s main avenues, the sidewalks and surrounding streets. They even organized to escort women out in claustrophobic moments, like in front of the emblematic El Caballito sculpture, when no one could move due to the crowding of bodies, women occupying public space that belongs to us by right and reality.

So many women came out, that even the absent were present. The thousands of disappeared and murdered women, in a country that accumulates more every day. Like Paula Camargo, her adolescent face smiling down from the palm tree where her picture is hung with her name and the caption: “2,752 days missing” –days counted with anguish by her mother who has never stopped searching. Or the loved ones of Marlen Cruz, who stands beside the flow of marchers holding larger-than-life photos of her daughter, Janette Tafoya Cruz, a victim of femicide, and Angelica Ambriz Tafoya, her granddaughter kidnapped by the killer.

“The State has done absolutely nothing more than mock our pain,” says Marlen: “I came to the march because all of us together make one voice asking for something that may be impossible in our lifetime–justice.” Through tears, she adds a message for her little granddaughter: “Angelica, wherever you are, I love you with all my soul and you deserve a life of love.”

The women present also marched on behalf of the thousands of women who were afraid to come, still unable to cope with trauma, pain or anger. Handwritten signs read: “For my grandmother, for my mother, for my sister, for my daughter, for me, FOR ALL OF US”.

Daniela López replied to the question of why she marches: “I come because I am literally fed up with the fact that we cannot go out into the streets… I come because many of my relatives were afraid of coming to the march, I come on behalf of my relatives, my friends, my clients–because I am a hairdresser– my nieces, my goddaughters, of all those who didn’t come because they’re scared of not coming home again.”

For every woman yelling slogans in unison, there is an unnumbered contingent of women behind them, those that remain invisible. With this physical strength and this moral strength, as a sign raised high read: “Nothing can stop this herd.”

Diversity in bloom

In early March in Mexico City the giant jacaranda trees turn lavender, seeming to endorse the purple-clad feminists. One of the tactics of the “progressive” patriarchy in government has been to attempt to divide and weaken the feminist movement. As feminists criticize unabated femicide and violence against women in the country, president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s response has often been to brand the movement as neoliberal, white, upper-middle class. While there are groups with these characteristics that call themselves feminists, the march 8, 2023 Mexico City march completely refuted the myth of a conservative movement led by the privileged.

Amid the diversity, if there was any predominant feature, it was the youth of the participants. Mexico’s women’s movement is not only strong and huge, it is regenerating, reinventing itself, with an energy incomparable with other times. Call it the fourth or fifth wave, it’s actually a tsunami.

Beyond the youth of marchers, the commonality was diversity. Women from many sectors marched together—students, workers, LGBTQ+, mothers with babies and elderly women. Micaela describes her own self-naming: “I am a trans, black, Dominican woman who has lived in Mexico for ten years and I am part of Frontera, a therapist collective.” She says that before she used to always attend the March 8 marches in the city.

Beyond the youth of marchers, the commonality was diversity. Women from many sectors marched together—students, workers, LGBTQ+, mothers with babies and elderly women. Micaela describes her own self-naming: “I am a trans, black, Dominican woman who has lived in Mexico for ten years and I am part of Frontera, a therapist collective.” She says that before she used to always attend the March 8 marches in the city.

“My last march was in 2019, but I stopped going to the marches because they were very violent marches for trans women–there was a hegemonic, transphobic, institutional, racist feminism that constantly humiliates us, stigmatizes us, criminalizes us, and in that march specifically, my physical integrity was attacked so I stopped attending the marches. But today I’m returning precisely because I realize that in the face of this feminism that denies us and that denies the plurality of trans women— that is, women come in many forms, we’re black, cis, trans, community-based, racialized, borderless—and that they deny us in particular, I have to be present. Because silence is not an option.” When I ask her if this year is different, she says that right-wing transphobic feminism persists, but “there are other groups of women who are inclusive, who have a broader, decolonial vision.”

The “expanded vision” Micaela describes seems to be part of an evolutionary  process of making room for more expressions of womanhood. Marchers broke ranks to give candy to the policewomen lined up along the route. Many dressed in blue watched the march with broad smiles, as if it were their own, their shields decorated with messages and multicolored drawings, thanks to the creativity of the protesters. The protesters made way for the men who crossed the street–hesitantly at first, then with relief at the courtesy. Some men marched alongside the women, others supported, reported or photographed the march without facing the aggressiveness that has characterized some past marches.

process of making room for more expressions of womanhood. Marchers broke ranks to give candy to the policewomen lined up along the route. Many dressed in blue watched the march with broad smiles, as if it were their own, their shields decorated with messages and multicolored drawings, thanks to the creativity of the protesters. The protesters made way for the men who crossed the street–hesitantly at first, then with relief at the courtesy. Some men marched alongside the women, others supported, reported or photographed the march without facing the aggressiveness that has characterized some past marches.

Joy, sorority, strength and plurality marked the march throughout its route. Only when they arrived at the seat of patriarchal state power, the National Palace, did police apparently primed to defend that power, launch tear gas into the crowd as a small group of women assaulted the barriers. Structural violence runs deep.

Movements in process

March 8 in Mexico is not only a show of strength and convening power for women’s movements, but also an opportunity to see how the movement is changing with the times. The pandemic marches reflected the health crisis—smaller, and marked by masks, frustration and repression. In this march, the changes were subtler.

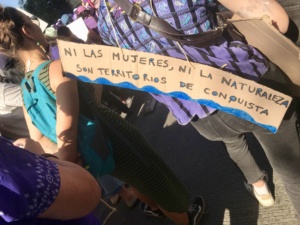

First in the organizational forms: women generally marched in groups, but not in formal contingents. The days of organized formations behind the big banner held by hierarchical leaders have given way to small collectives carrying personal, handmade banners, individual women motivated by their own life stories and united by a decision to transform them. Students who identify with the cause rather than the institution where they organized. Women workers who march against sexual violence and discrimination in the workplace, rather than as representatives of their jobs or sectors.

First in the organizational forms: women generally marched in groups, but not in formal contingents. The days of organized formations behind the big banner held by hierarchical leaders have given way to small collectives carrying personal, handmade banners, individual women motivated by their own life stories and united by a decision to transform them. Students who identify with the cause rather than the institution where they organized. Women workers who march against sexual violence and discrimination in the workplace, rather than as representatives of their jobs or sectors.

And amid the protest, they take care of each other. They form chains of hands, and stretch ribbons to hold on to so as not to lose anyone in the crowd. In a nation where the majority of the reports of violence against women human rights defenders identity state agents as the perpetrators, they chant in unison: “The police don’t take care of me, my girlfriends take care of me”.

Laura Carlsen is the Director of the Mexico City-based Americas Program, Mexican/US journalist, political analyst and writer.