The product of exclusive, closed-door negotiations, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) represents the final sale of Mexico to the multinational corporations. In other words, a farewell to whatever national sovereignty still exists, and the elimination of any possibility of recuperating food sovereignty.

The product of exclusive, closed-door negotiations, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) represents the final sale of Mexico to the multinational corporations. In other words, a farewell to whatever national sovereignty still exists, and the elimination of any possibility of recuperating food sovereignty.

Today, Oct. 16th, the UN celebrates World Food Day, and Via Campesina observes a global day of action for food sovereignty against transnational corporations. Meanwhile, campesino and indigenous organizations reject the TPP and prepare to demand that the Senate of the Republic not ratify the new trade agreement, and that it be put before a public consultation.

Small and medium farmers, members of the National Union of Autonomous Regional Campesino Organizations (UNORCA) and El Barzón, stated in communiqués that the TPP would aggravate the country’s dependence on external sources of food, and would make food sovereignty impossible.

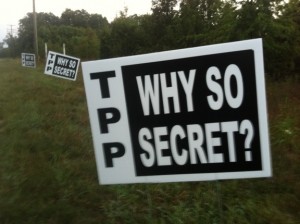

Transnational corporations, a handful of technocrats and businesspeople have participated in the backroom negotiations. Although the documents are not publicly available, it is obvious that the process has been developed in a discreet manner, with the goal of guaranteeing the interests of the global economic elite, at the expense of the peoples of the nations involved. The drafts that have been leaked show that the TPP will be worse than its predecessor the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The TPP, like NAFTA, is not a “free” trade agreement. Its main provisions are not the reduction of tariff barriers. Rather, both agreements emphasize creating and extending the privileges of multinational corporations and permitting these corporations to place themselves above governments, laws and judicial rulings to avoid negative impacts on their investments. Thus, free trade agreements become a threat to the environment, food sovereignty, public health and other basic rights.

Specifically, the main concern of the experts and farmers mentioned above is that the local laws and judicial systems of the nations who are signatories to agreements like NAFTA or the TPP are subordinated to tribunals established by the treaties. These tribunals make no guarantee of the right to due process, and are generally more favorable to private industry than to the public interest.

“Most people would be worse off as a result of the agreement,” writes Mark Weisbrot of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “Even worse, the TPP’s provisions that strengthen and lengthen patent and copyright protection, according to the drafts that have been leaked, would have even more of an impact in the upward distribution of income. It is no exaggeration when opponents of the TPP refer to the agreement as a ‘corporate power grab.’”

According to studies by the Americas Program, Mexico did badly in the first 20 years of NAFTA. “Since the agreement went into force in 1994, the country’s annual per capita growth flat-lined to an average of just 1.2 percent—one of the lowest in the hemisphere. Its real wage has declined and unemployment is up,” wrote its director Laura Carlsen in the New York Times. It also generated unemployment and wage loss in the United States.

In this context, Weisbrot points out, “The lessons from NAFTA are a big part of the reason that the Obama administration is having so much trouble getting the TPP past Congress. Of course the TPP’s proponents have also learned lessons from NAFTA: That’s why its contents have been kept secret from the public throughout the negotiations.”

For UNORCA, Mexico, especially its rural areas, is the victim of a new offensive of huge dimensions on the part of multinational corporations. However, almost no one is paying attention. “Another betrayal on the part of the Mexican government is at hand,” affirmed the organization’s national director, Olegario Carrillo.

Most people have never heard of the TPP, and most people who have heard of it don’t know exactly what it is. This is no accident. Even though an enormous quantity of people, from various countries on both sides of the Pacific, including Mexico, will be gravely affected by the agreement, their opinions are not being taken into account.

The TPP contains 30 chapters, which include materials about the environment, sanitation policy, access to markets, rules of origin, obstacles to trade, private defense contracting, competence, public finances, services, investment, e-commerce, telecommunications, financial services, intellectual property and labor issues. It also incorporates the so-called horizontal issues: regulatory coherence, competitiveness, and the development of small and medium businesses. And, at the industrial level, the agreement involves the automobile, textile, pharmaceutical and agricultural sectors.

According to Beatriz Plaza and Gorka Martija, of the Observatory of Multinationals in Latin America, the key points of the agreement are:

The prohibition of requirements that genetically modified products be tagged.

The protection of patents and copyright, including generic medications, favoring transnational pharmaceutical corporations by reinforcing industrial property.

The mutual recognition of various regulations, which implies the application of the regulations that are guarantee the least for the population and are most beneficial to multinational corporations.

The reduction of public contracting in favor of privatization (reduction in the purchases of local products in favor of international products).

Environmental regulations (issues related to nuclear energy, contamination and sustainability).

And financial deregulation.

In effect, the TPP is not about commerce, nor is it about “free trade”; it is about power and control. The power that is progressively taken away from the people, and captured by a class of magnates and investors in transnational corporations who, today more than ever, have more power than governments and nations.

The TPP creates a system of international commercial tribunals that will allow transnational businesses to ignore and annul the national laws of any signatory nation. These tribunals are extrajudicial—that is, their authority is derived from outside and goes over national justice systems. Their members are not elected and are not accountable to the citizens.

The laws that will be subject to this new agreement include the right to food, intellectual property, food security and safety, subsidies, environmental norms and practically every regulation that affects the corporations’ operation. The changes in the institutional and legislative configurationwill have a larger impact on access to food for part of the Mexican population, and in particular, the most empoverished sectors.

If a country passes a law to protect its citizens, to guarantee them access to quality food or to reduce contamination, a multinational that sees itself as affected will be able to appeal to one of the tribunals. The rulings will be binding. It won’t matter if the people have elected their legislators democratically to approve such laws.

“We reject the participation of the Enrique Peña Nieto’s government in the negotiation of these secret accords in favor of the transnationals and against Mexico,” said the UNORCA.

The Mexican government, who came to the negotiations after various agreements had already been reached, and who subordinated itself to the interests of the US government and the transnationals, makes reference to the supposed benefits for Mexico that the signing of the TPP will bring. President Enrique Peña Nieto called the TPP, in a tweet, “a forward-looking agreement with which Mexico will strengthen its cooperation with the world,” as if integration for integration’s sake were beneficial. He added, “the TPP will translate to better opportunities for investment and high-paying jobs for Mexicans.”

To prove him wrong, we only need to look at NAFTA. Twenty-one years after it came into effect, rural areas are a disaster. Their contribution to the GDP has declined, migration from rural areas to US cities has grown to alarming levels and the economy has been stagnant, with a yearly growth rate of 2%, which population growth reduces to zero, and which is even worse for the agricultural sector. The country’s food dependency has risen to 42%, according to official sources.

El Barzón says that in most regions NAFTA has not generated employment growth, while the export growth has been confined to the reduced production sector, which relies on cheap labor, precarious employment and imported inputs, both in agricultural and manufacturing.

Treaties harmful to the countryside

Mexico has signed 11 free trade agreements with 46 countries, 32 Agreements for the Promotion and Reciprocal Protection of Investments (APRIs) with 33 countries and nine limited-scope agreements (Economic Complementation Agreements and Partial Scope Agreements), under the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI).

Mexico has no shortage of free trade agreements. This is the proof that these agreements do not offer solutions to the crisis of food production and the general economic crisis, but rather seek to restore national productive capacity to take advantage of trade relationships with other countries on more equitable terms.

“Mexican producers come into contact with 700 million consumers. Soon, free trade agreements will allow us to serve another 500 million consumers. However, the weakness of national production and the existence of a monopolistic infrastructure in national markets has prevented our country from achieving higher degrees of development,” El Barzón said.

The TPP not only does not offer solutions, but it also will severely affect producers of rice, wheat, milk and meat, deepen Mexico’s food dependency and drive thousands of producers and entire regions of the country into bankruptcy.

As in NAFTA, the agricultural sector will be one of the sectors most affected by the TPP. Our country has suffered collapses of production in rice, meat, milk and wheat due to the rise in imports that has made us completely dependent on the exterior.

The TPP and the conditions under which the total opening of tariff barriers will take place will lead to the practical disappearance of the small and medium producers that find themselves still tied to these products and regions of the country.

The TPP will only bring benefits for Mexican companies that already have a multinational presence. The only benefactors will be the Visur Group, through its business Su Karne, the Lala and Alpura companies, Bimbo and the Gruma Group, who have achieved growth and international presence through the domination of national markets, and the physical and financial support they have received from the government.

Here are some of the impacts on each product:

Rice

In Mexico there are only 3,800 rice farmers and we are 80% dependent on imports to meet domestic consumption. The indiscriminate opening being projected in the TPP and the very short deadlines for tariff reduction will cause the ruin of these growers and severely affect the states of Nayarit, Michoacán, Morelos and Veracruz, among others. Forced to compete with Vietnam, who produces 28 million tons a year, and Japan, who produces with 7.9 million tons a year, what shall we do with the 232,000 that we produce in Mexico?

Wheat

Today Mexico suffers from an approximately 70% dependence for wheat consumption, and is only able to produce 3.6 million tons annually. The United States produces nearly 60 million tons a year, due to high government subsidies. It was this disadvantageous relationship that has led to domestic producers of wheat to virtually disappear.

The new advantage that the TPP would give the United States and Canada would severely affect Sonora, Baja California, Guanajuato, Sinaloa, Chihuahua and Jalisco where farmers suffer every day from the lack of government support and increasing production costs.

Meat and milk

The participation of New Zealand, tariff reductions and the much shorter terms will destroy thousands of Mexican producers, with a 49.6% dependence on imports, 90% of which come from the US, 5% from New Zealand, and 1.5% from Canada.

In the case of meat, 87% of imports come from the United States and 11% from Canada. The European Union produces 11.05 million tons of meat annually. In Mexico there are 1.5 million beef producers, with a production of 1.8 million tons. The main producing states are Veracruz, Jalisco, Chiapas, Sinaloa, Sonora, Baja California, San Luis Potosi and Michoacán.

Finally, small and medium producers reiterated their condemnation of the secrecy and the secrecy with which the negotiations have been conducted and express their dissatisfaction that the concerns of only some leaders of the National Agricultural Council and representatives of big agribusiness companies in the country were taken into account.

Several peasant organizations have called on all those affected by the TPP to join efforts to mobilize the population and prevent the imposition of the interests of large agribusiness corporations.

They demand that the Senate not act as a rubber stamp for the executive, but that it analyze in the agreement in detail. And they demand a public debate with all concerned sectors and a binding national public consultation.

Alfredo Acedo is a journalist and director of communications of the UNORCA. He is a contributing writer to the Americas Program www.americas.org

Translation by Simon Schatzberg Photo: Global Trade Watch