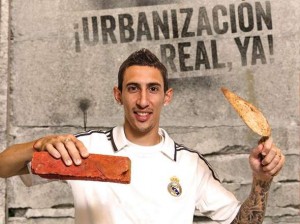

La Garganta Poderosa: Voice and dignity from below

The villas of Buenos Aires–the poorest neighborhoods in the city, self-constructed, self-defended during decades of state harassment and real estate speculation–produce one of the best publications around: La Garganta Poderosa.